Momoko Seto’s ‘Dandelion’s Odyssey’ Is An Experimental Animated Feature Unlike Anything You’ve Seen Before

Dandelion’s Odyssey (Planètes in its original French title), is an animated film like no other, the latest by Paris-based Japanese artist Momoko Seto. Yet it’s already the fifth iteration of Seto’s Planet artistic voyages, a journey through nature, size, and scale she started back in 2008 with her first short Planet A, and carried on to this — her first feature.

Bridging between experimental art, documentary, and animation, Seto’s works explore the world around us and transcend it into cinematic experiences unveiling the infinite diversity of life and matter. Her previous work tackles everything from living salt statues to eerie mushroom thrillers to prawn porn and octopus love stories.

Dandelion’s Odyssey brings these artistic explorations to another level of experimentation with a daring fusion of time-lapse photography, robots, cg animation, and macro-photography, among other techniques. Following four dandelion seeds thrown into the cosmos by what appears to be nothing less than humanity’s last folly, the dialogue-free film takes its viewers on an alienating yet familiar journey, as nature and science-fiction become intertwined in a breathtaking visual fantasia.

Produced by France’s Miyu Productions and Ecce Films, Dandelion’s Odyssey premiered at Cannes’ Critics’ Week, where the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) awarded it best first feature in a parallel section, Directors’ Fortnight, or Critic’s Week. Cartoon Brew spoke with Seto ahead of its world premiere in Cannes. The film will also screen next week as part of the feature competition at Annecy.

Cartoon Brew: How did you start your own odyssey in cinema?

Momoko Seto: I grew up in Japan, then came to France to study fine arts in Marseille, where I focused on video, art installations, and experimental cinema. After a filmmaking major at the California College of the Arts, I came back to France and did a post-graduate at Le Fresnoy, where I made Planet A as my student short. What I wanted to explore was how technology could help us create, and find other ways of making art and cinema.

That path leads us to Dandelion’s Odyssey, which bridges the gap between real images and science fiction. What compelled you to tell this story?

Two things. First, you mentioned that it is a story, a seed’s story. I wanted to share a plant tale, where plants are the main character, yet without mimicking Disney’s Silly Symphonies with their human-like trees. I was aiming to tell what it is like to truly be a plant, to become vegetal. Because when you take this point of view, you can switch perspectives. A seed’s journey is one of wandering between ecosystems, some hostile and dangerous, with the ultimate goal of finding the right spot to settle oneself. And in telling this tale, you change size, time and movement as a whole. It’s wildly different than just changing the human scale, it’s a whole other feeling that I wanted to share with this Indiana Jones-like plant adventure.

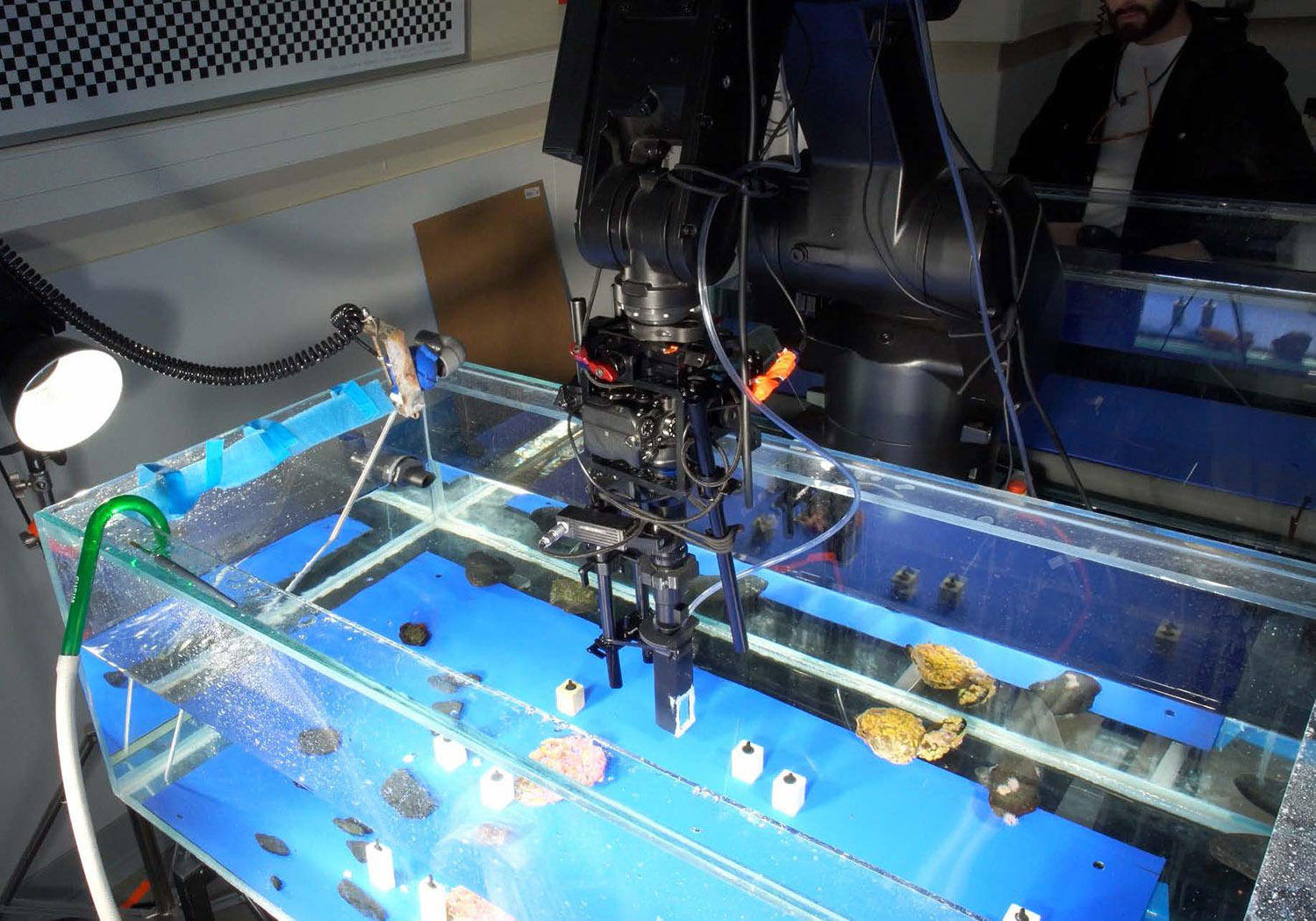

True nature has always been fascinating to me, with its mesmerizing shapes, stylized colors, and beauty so complex that humans can’t reproduce. My idea was to draw from this infinite source with dedicated tools, in order to create a whole new perspective of this real yet unknown universe. For that purpose, we used time-lapse, macro-photography, robotics, periscopes, drones, and a wide range of techniques that were created for the film, so these animated seeds could become part of a world where time and space were completely new to the viewer.

How did you approach the making of this film?

I already had an established style, which I built with my four previous Planet shorts and fifteen years of experimentation. To me, time-lapses and slow-motion sequences have to be very smooth, with the idea that one cannot guess if time has been slowed or accelerated, creating a beautiful reality. Dandelion’s Odyssey is a project that we spent three years writing, as we aimed for a strong fictional narrative. It’s at that stage that I inserted the “actors” I wanted to portray in the film, such as urchins, luminescent squids, the frozen frog, or the desert that appears at the end of the film, which we created with tree barks and sand. All these motifs were partly based on my previous explorations, and the new grounds I wanted to discover.

We then turned our 70-page-long screenplay into sequences and listed all the image material we would have to shoot or create. Each sequence had to be carefully designed through mood boards to ensure that lighting and perspectives would match. To this purpose, we created a whole animatic of the film to define camera movements, optics, and all the necessary info before going into shooting.

Each shot is made of five layers. There’s the set, decor, animals, background, time-lapse, and animation, and this varies between sequences. For example, we shot the landing butterfly in Japan, which was overlaid upon a set built and shot in France with the praying mantis already present. Moving plants — filmed through another time-lapse — are shot in front of a bluescreen, and also inserted in the shot.

Animation comes at the very end of this process, as another layer where we integrate the dandelion seeds. First through layout, and then through animation created by a whole team of Belgian animators helmed by Pixar and Aardman veteran Guionne Leroy, who gave life to our four characters to create the final look of the film.

Can you share some facts and figures about this unique shooting process?

Our overall budget is roughly 4.4 million euros (USD$5 million), with three years of writing, two years of financing, 260 days of shooting, two years of post-production, one year of animation, and two years of sound design and music. During this journey, around 200 people collaborated on this project.

How does one finance such a film?

We went through the classic French channels, with public funds such as CNC, broadcasters including Arte and Canal+, and regional funds such as Région Île-de-France, Aquitaine, and a co-production with Belgium. Funnily enough, it’s a project that had a huge make-or-break status. We received the CNC’s help unanimously on our very first try, even though this is my first feature and there are a lot of projects competing for this funding, and Arte as well as Canal+ were also received on first submissions.

Obviously, we got some negative answers. I mean, for a project like this — no dialogues, big technical challenges, narrative constraints, and plant protagonists — it is impressive to see that it was always either general enthusiasm or shared skepticism. I think being supported by Miyu Productions, a solid and trustworthy company with a unique DNA, also helped gather trust among our financial backers.

Going back to sound design, how did you tackle this crucial part of your film?

Inventing this language was all made possible by the collaboration of Nicolas Becker, whose career ranges from Foley artist in the 1990s to the sound design of international acclaimed projects such as Gravity or Sound of Metal. Nicolas has the ability to invent sounds where there is none, which is exactly the case in the plant’s realm. Our visions matched very quickly.

Later on, Nicolas himself told me he wanted to work with composer Quentin Sirjacq, with whom he had already been working for two years. They aimed to build a soundtrack where sounds become music, where silences become songs. Together, we shaped what could be the sound of this particular future, a mix between ancient and futuristic tones. Quentin then composed an orchestral soundtrack but with rare instruments such as French glass organ “Cristal Baschet” or theremin-like “Ondes Martenot”, bringing these seldom heard analog instruments into a digital soundspace.

What are some unique aspects of the film that you’d like to further discuss?

I think that, due to the nature of this odyssey, many viewers will think that at least half of the images are special effects, but this is hardly the case. Vfx come to back up images, but all you see on screen is real, from the frozen frog to the fascinating praying mantis or the galaxy of luminescent squids.

Another aspect that’s dear to me is the sound of our four protagonists. It’s very subtle, but their “voices” are created with four layers of human breathing and hushing. It’s almost subconscious, but these ups and downs give the seeds a rhythm and a life which makes them very relatable. It brings you back to your childhood, where you used your mouth to create whole atmospheres and literally breathe life into your inanimate toys.

One thing that strikes the viewer head on is the bleak opening that triggers this dandelion’s odyssey. Can you elaborate on this choice?

It’s the little part of my film that makes a political stance, but to me it remains a subtle one. What I wanted was to create a dystopian setting where humanity — which is not the subject of this film — disappears because of itself. Life on our planet doesn’t disappear because of a meteor, or climate change, but because of this very real atomic bomb that burn the Earth and force the seeds to undertake this journey.

This odyssey is about planets, plural. How one travels to another world and can maybe start anew. Or maybe it’s more of an introspection, going back to what was before. It remains unclear, but it also brings a sense of relativity to this story. Humanity itself is very young, in terms of Earth’s history, both past and future. By switching scales, and telling this story through the perspective of plants, I wanted to question our own ephemeral nature.

Who do you envision as the audience for this film?

I think it’s for all types of audiences. My children, and other children as well. Sharing the beauty of nature is something that appeals to everyone’s inner child, and unveiling its secrets can be a magnificent journey for everyone. I wanted to say that one’s ability to marvel was not something that should be denied or deemed stupid and childlike. It’s necessary to protect oneself, and to protect nature as well. These are not exotic landscapes or plants from Brazil, animals from the deep Philippine forests. These are very common creatures that surround us, that we can stop by and still be amazed by their beauty.

Another thing that was pinpointed to me by a journalist, who was brought to tears by the film, is that it’s also a story about migration, about leaving your world behind, trying to find another one to build a future. And that’s an aspect of the project that is very dear to me. As a Japanese woman living in France, I undertook my own personal migration. Each and every one of us wants to find their very own oasis, a place they can call home. Sharing these moments of solitude, these separations, and the journeys you undertake to achieve this goal is something very personal that I wanted to share and that I feel every time I go back to the film.

.png)